Sub Saharan education issues are complex. The solution is simple.

28 November 2018

The 2018 World Bank Report Facing Forward: Schooling for Learning in Africa (Full report; Overview) begins by arguing that Sub Saharan Africa is ‘behind’ other regions of the world in developing its knowledge capital; the ability of individuals and nations to fully realise their talents and potential. The timing of their report is critical, with Sub Saharan Africa’s youth population set to boom, as much of the rest of the world goes into population decline. By 2050, one in three people under the age of 18 will be African.

Africa’s ‘demographic dividend’ has massive potential and is occurring in parallel to huge changes and challenges that will define the future of the Continent. Africa’s economies are becoming more diverse, integrated and productive whilst its populations become more urban, affluent and better connected.

Education – or lack thereof – will underpin the direction of Africa’s growth. It will be the single biggest factor in determining the future cohesion and prosperity of Africa – a Continent that is experiencing remarkable social, political, economic and demographic changes.

From a pan-African perspective, a better educated population will be more more resilient, more equal, more mobile and have fewer children. The Facing Forward report focuses on 46 of the 54 countries in Africa – those defined as Sub Saharan Africa. It focuses on knowledge capital and reflects a broader shift occurring in the global education sector from measuring access to measuring outcomes. This is partly driven by the reality that whilst enrolment has been increasing successfully – in places – we have not seen a parallel increase in learning. This is the so called ‘Learning Crisis’ heralded by news that 56% of children, or 387 million, won’t achieve minimum proficiency levels by the time they should be completing primary education.

The status of education in Sub Saharan Africa

Good progress has been made in enrolling children from Sub Saharan Africa into primary education, but more needs to be done. To catalyse the change on the scale required every child will need to complete at least ten years of basic education and be at the very least competent in literacy, numeracy and science. It is no longer enough, just to be in school. Plus, many more will need to be educated beyond just a basic education to enable Africa’s future path to prosperity.

Enrolment in primary education is decreasing in approx one-third of Sub Saharan African countries

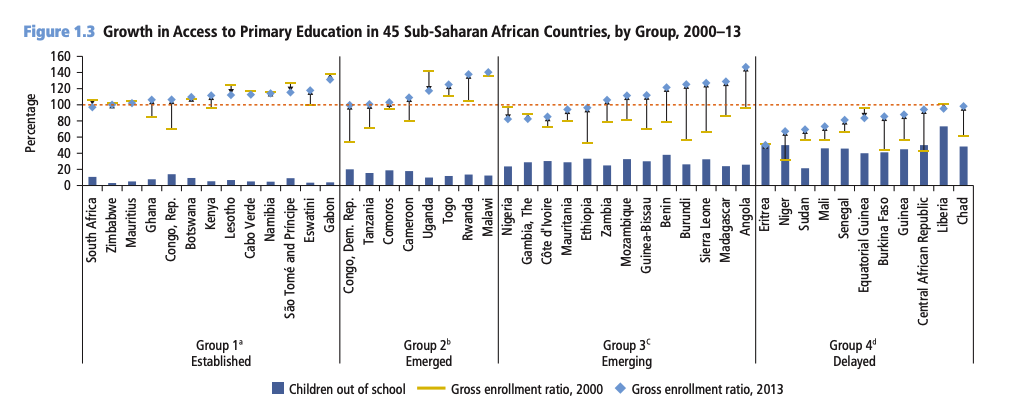

While improved enrolment is to be celebrated, we must recognise that between 2000-2013 the Gross Enrolment Rates (GERs) actually went down in 14 out of 45 countries. In total, more than 50 million children remain out-of-school in Sub Saharan Africa.

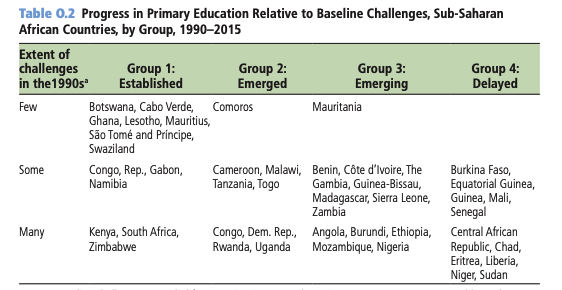

Looking at Figure 1.3 above we can see that in the countries where Bridge works — only Kenya saw an increase in gross enrolment between 2000-2013. Uganda, Liberia and Nigeria experienced a decline. Together, these four countries are typical of the education landscape in Sub Saharan Africa, and represent a good cross-section with one in each ‘Group’ (see Table O.2) according to the maturity of their ‘challenges’.

The report argues that for those in Group 2 and 3, such as Uganda and Nigeria, education enrolment remains “unfinished” — which means they have expanded access but need to ensure that children complete their primary education; and of course that they emerge literate and numerate.

For countries in Group 4 like Liberia, the focus should be on improving access to education in First Grade and maintaining a high retention rate through the basic education cycle. Tackling cultural challenges that see children accessing school late in their development; leaving school to help support family subsistence – or due to early marriage – and ensuring consistent attendance are persistent issues.

For Group 1 countries like Kenya, retaining the small percentage of students who are dropping out means having targeted schools and programmes for children from underserved, disadvantaged and vulnerable backgrounds i.e. slum or remote and rural communities.

So, the challenges fall under four themes of:

- Retaining pupils;

- Increasing access to schools;

- Reaching the most vulnerable; and,

- Increasing the quality of learning.

Essentially, each country needs to ensure that every child goes to school, completes schools and leaves at least competent in basic literacy and numeracy. Depending on which country you look at they have successfully achieved some of these objectives, but not all.

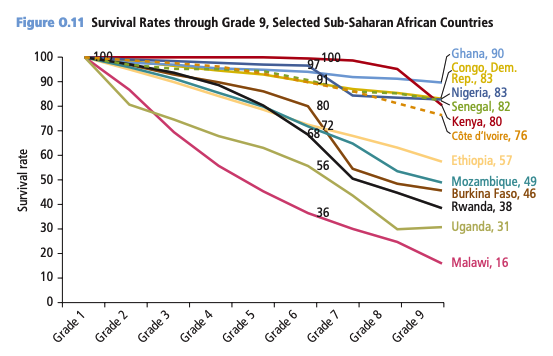

Retention

Retention is a challenge that affects the poor, rural and female pupils more than any others. Figure 0.11 below shows the ‘Survival Rate’ of 12 countries in Sub Saharan Africa – completion to Grade 6 or 9, regardless of repetition and includes Kenya, Nigeria and Uganda. The percentage of those that make it to Grade 9 in Uganda is just 31%, compared to 80% or 83% in Kenya and Nigeria, respectively.

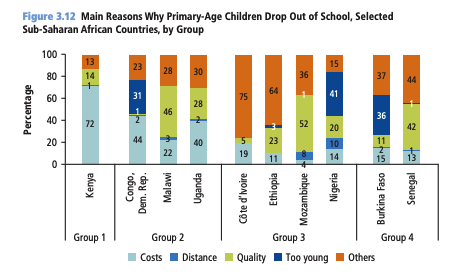

Using household data from the 12 countries (Figure 3.12 below) some of the most common reasons for dropping out of primary education are cited as: high cost, poor quality, and distance to a school.

Causes are often interlinked and costs can be both direct or indirect, for example, in rural areas there are opportunity costs associated with sending children to school who could otherwise be doing chores, tending cattle or looking after siblings.

For girls, marriage and pregnancy is an additional factor and the biggest reason for leaving school amongst girls living in Uganda. For some Sub Saharan African families it’s reported, girls who have reached puberty are viewed as “marriageable” and often forced to abandon their education.

Increasing access

Facing Forward outlines concrete policies to improve basic education in Sub Saharan Africa:

Leveraging the private sector: Expanding the number of schools to meet demand. Bridge is currently working in partnership with the Government of Liberia and Edo State in Nigeria to manage schools and train government qualified teachers, respectively.

Revising curriculums: Many curriculums and corresponding lessons taught in Sub Saharan Africa date back to the 1970’s. Major reforms are typically unpopular within the educational establishment but increasingly necessary to link education with the right outcomes for a modern African society. Bridge uses tablet computers (‘teacher guides’) that deliver up-to-the minute, locally relevant lessons; an approach used by USAID in Pakistan and elsewhere.

Using technology: Increased connectivity in Africa has been accompanied by a fall in the cost of the devices used to access networks. Sub Saharan Africa is currently the fastest growing region for mobile connectivity. Faced with the constraints of infrastructure and connectivity, any new technology must necessarily be iterative or otherwise designed to work effectively in a low-infrastructure environment. For Bridge, and others, this technology challenge has already been transformed into an edtech innovation opportunity.

Technology also impacts on another solution, bringing schools closer to rural (and excluded) communities: Children in rural areas have less access to education. For example, in Liberia, just 50% of school aged children in rural areas go to school. Using technology like Bridge’s, classrooms are consistent in terms of quality, accountability and learning wherever they are be it rural, urban or ephemeral such as a refugee settlement.

Increasing teacher competency: Utilising technology and redesigning instructional materials alone won’t improve outcomes. Changes must be accompanied by training and support opportunities for teachers and school managers to develop their professional competencies.

Six ways to Increase quality

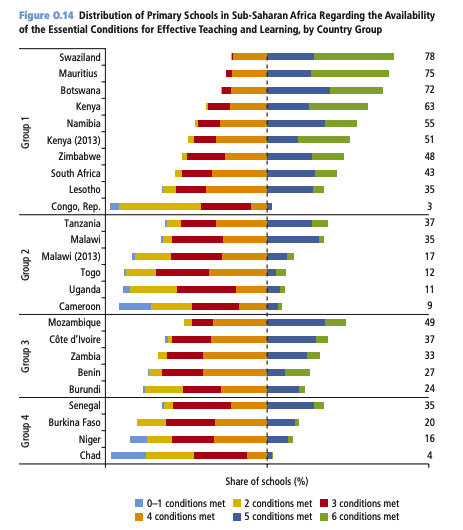

Many primary schools lack ‘minimally conducive conditions’ for effective teaching and learning. A trained and/or qualified teacher equipped with the right pedagogical knowledge and skills is essential, but five other features of schools also matter:

- Low pupil-teacher ratio of no more than 50 children per teacher;

- Access to textbooks (read why this matters);

- Basic sanitation, such as toilets and different toilets for boys and girls;

- Regular attendance in class, including from teachers (teacher absenteeism is between 25-30% in Kenya and Uganda); and,

- A school climate free from abuse and violence (Bridge has always had a strict no corporal punishment rule, wherever we operate).

Taken together, these six conditions are what the report believes are a good benchmark for assessing the quality of education in Sub Saharan Africa. Of those countries where there is data, we can see that at best just 78% of primary schools qualify as meeting the essential conditions for teaching and learning. This is as low as 11% in Uganda.

Reaching every community

Sub-Saharan African countries face unique challenges relating to teacher support and management; the single biggest factor affecting teaching quality and therefore, learning outcomes. The current pool of teachers in many countries is a wide mix of trained and/or qualified teachers who have an extremely variable grasp of content knowledge and skills. In addition, schools in Sub Saharan Africa are plagued by chronic absenteeism or ‘ghost teachers’ on the government payroll.

Teachers suffer from a lack of systematic supervision and support at the individual school level. In this context, it’s crucial to provide a coherent approach to training and supporting teachers alongside an effective strategy for the ongoing engagement, support and development of staff.

Typically too, schools in poorer communities tend to have higher pupil-teacher ratios; less supported teachers; fewer books, learning materials and less educational equipment. Such schools also have fewer amenities that make them attractive to teachers — increasing the bias of teaching staff for urban and more affluent communities. For example, many governments struggle to retain teachers in rural communities once they have completed their initial assignments. One solution is to recruit teachers from the communities themselves, like Bridge does.

Conclusion

Progress has been made towards more and better education in Sub Saharan Africa and this should be celebrated. However, the causes and consequences of education inequalities are an evolving blend of quality, cost, attitudes and the success or proximity of solutions (if any) combined with the four challenges of retention, access and the equity and quality of learning.

By adopting the right innovation, like Bridge, it’s possible to solve all four — increase access to quality learning by driving up teaching and lesson quality; reduce costs and increase proximity to good schools, and using low-infrastructure technology; track attendance, lesson progress and comprehension and deliver targeted improvements anywhere in Sub Saharan Africa — city, slum, rural and highly mobile refugee and conflict environments.

What we can conclude as an organisation operating across four countries and the whole spectrum of education issues in Sub Saharan Africa is that our model is working. This is in part because it’s accountable to our parents and government partners but also because we have long recognised — as Facing Forward does in its report and recommendations — that it’s necessary to systematically improve access; measure and improve learning, and; retain pupils and teaching talent – everywhere it’s needed.

Crucially, we need to have the capacity to scale up what’s working – in an evidence based way, void of dogma and laser focused on the needs of ordinary Africans, and by extension the whole of Sub Saharan Africa.

The solution is simple. Look at what’s working?