A Love of Books Leads to Literacy and Learning

25 February 2018

Reading is fundamental to opportunity, prosperity and even better health; it’s an education bedrock. Yet, around the world, most children aren’t able to read well, and many have nothing to read or can’t read at all.

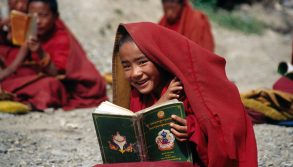

When most people think about books they think about storybooks, full of adventures and new worlds that transport readers. However, there is another form of book that doesn’t get talked about enough but is equally important – the school textbook.

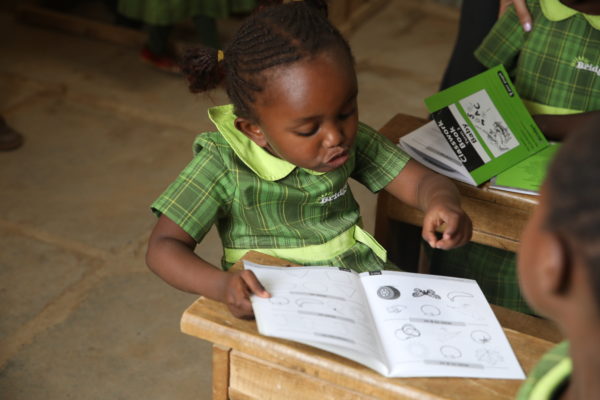

There are two major drivers holding education back: a lack of access to learning and a lack of quality teaching. Walk into almost any classroom in Sub-Saharan Africa and you will see very few books available. When it comes to textbooks, it’s not uncommon to have lots of children crowded around a book trying to follow the teacher. This significantly impacts learning. Well-designed textbooks in sufficient quantities are only second to engaged and prepared teachers, as the most effective way of improving learning outcomes (GEM: 2016).

A textbook plays a key role in classrooms, they are used by teachers to guide lessons, supplement teaching and support pupils. It’s important that they are age appropriate and designed to support the lesson being delivered. Fundamentally, they also support the conversion of key Ministry and Government education policy aims into practical lesson plans and activities. Yet, despite this fundamental need, many classrooms across Sub-Saharan Africa simply do not have enough, that’s if they have any at all. Their quality and effectiveness can vary for several reasons, including the clarity of instruction, print quality, age and condition of the book. For many, literate or not, the sad reality is that they can have no access to textbooks at all.

The textbook is in many ways emblematic of the distinction between access to education (“in class”) and access to quality education (“in class, and learning”). If a classroom is devoid of effective textbooks it is likely that very limited learning will be taking place.

The problem of limited availability isn’t always a problem of scarcity. As textbooks are such a valuable asset the World Bank (2010) report highlighted that even if they are available, this doesn’t always mean they are used! The report found that in countries like Malawi, teachers were reluctant to hand them out for fear of damage or loss. In Sierra Leone, concerns about future supply led to hoarding of textbooks and them not being used (Sabarwal et al., 2013 [Unpublished]).

The lack of books is particularly acute in developing countries that have experienced rapid enrolment following the implementation of Government policies designed to increase access. Kenya’s re-introduction of free primary education in 2003 is an example of this. They simply haven’t been able to produce enough well-designed learning materials to equip pupils and classrooms with enough books to keep up with their policy rollout.

So, why are books not more easily available in classrooms worldwide? Cost is an obvious factor affecting availability, and the cost per book can vary dramatically through a combination of cost factors including manufacturing, procurement; publishing; distribution; storage; raw materials; importation and corruption.

All of these combine to influence the price at a local, national and regional levels. In Viet Nam, by leveraging competition in the domestic publishing industry, the price per book is markedly lower than in Sub-Saharan Africa; $0.33-0.66 compared to $2.00-4.00, respectively. An example from Rwanda and Kenya is illustrative of how local dynamics can have a further influence on cost. Despite both countries using commercial distribution to deliver books, the unit cost per book is much higher in Kenya. This is due to publishers in Rwanda delivering direct to schools, whereas in Kenya delivery occurs through a bookseller middleman (Read and Bontoux, 2015).

Corruption can also manifest itself through the award of contracts and/or the provision of low-quality books at a higher cost in order to inflate profits. Finally, cost-saving measures resulting from corruption, small budgets or both, such as low-quality paper or poor binding has a direct impact on the durability and utility of textbooks (DFID: 2010).

One response to these problems has been to break the government monopoly on textbooks. In 2002, Uganda started to work with a private publisher through a competitive process which saw the cost of textbooks fall by two-thirds whilst increasing quality (Fredriksen, 2012). It is also commonplace at sso-called‘free’ public schools for parents to be charged for textbooks, disadvantaging those children whose parents can’t afford this hidden expense.

A 2012 study from UNESCO looked at the average cost of education across 12 African countries and found that school supplies and learning materials alone accounted for 34% of the total education spend of a household; in contrast to fees at 55%. This same study found the cost of supplies and materials disproportionately affected poorer households, with some households – often richer – more likely to pay higher fees for better resourced schools, therefore spending less on supplies and materials.

The availability of textbooks and their impact on learning naturally has an impact on a child’s ability to go to the library and get lost in stories about swashbuckling adventure.

The textbook is instrumental and more focus needs to given to ensuring that a child’s education is not adversely impacted by the absence of effective, well-crafted books in their classrooms. At Bridge, additional textbooks are carefully designed by our team of in-country academic experts, to supplement those provided by national government’s. They follow the host country curriculum; include local characters and situations that pupils can relate to and are always age appropriate. The content in these textbooks is reviewed and updated regularly match our detailed Teacher Guides. This guarantees that what the teacher says and writes is the same as what appears in the child’s book, for the most effective learning outcome.

A study in 2013-4 (Bridge: 2015) found that Bridge pupils in Kenya had gains in reading equal to 64 additional days of learning in a single academic year.

In July 2017, halfway through its first year, the Learning in Liberia report revealed that Bridge PSL pupils could read 7 more words a minute and answer 6% more questions correctly about the story they just read. Further, 17% of Bridge PSL public school second graders met reading fluency benchmarks for the first time, compared to only 4% of second graders at traditional public schools. At the end of PSL’s first year, a randomised control trial by the Center for Global Development found Bridge PSL pupils had reading gains equivalent to a whole additional year of schooling when compared to non-PSL government schools.

The Bridge PSL textbook has been so successful in Liberia that recently we provided over 2,000 books to More Than Me – another PSL partner. These books will enable hundreds of Liberian children to access an improved early childhood education; whereby learning to read they’ll be put on a path in life to one day write their own stories.

Alexandra Fallon, Chief Academic Officer, MoreThanMe said of the books, “We were so impressed by the quality and accessibility of Bridge textbooks that we made the decision to purchase them for the early childhood grades in all of the PSL schools that we work with. Teachers and students have been equally delighted by these powerful learning resources!”

Teachers at a More Than Me Academy with new books

More Than Me Staff, Aaron Ballah showing Teachers at Gborketa Public School the new learning materials.

As we celebrate World Book Day, let’s remember that the entry point to a love of reading and a love of books is a good education – and a good education depends on a good well-crafted textbook for each and every child.