Teaching and Learning International Survey

21 June 2019

Every five years, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation & Development (OECD) produces the Teaching and Learning International Survey (TALIS). TALIS is an international, large-scale survey of teachers, school leaders and school environments; this time around it featured 48 countries, 31 of which are OECD countries.

One of the main objectives of the TALIS is helping countries monitor and report their work around the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). This applies to Goal 4 in particular, which seeks to ‘ensure inclusive and equitable quality education and promote lifelong learning opportunities for all.’ Following the publication of the report, an Education Fast Forward (EFF) debate was held, where leaders from across the world of education discussed the findings and considered what the next steps should be.

What motivates teachers to teach?

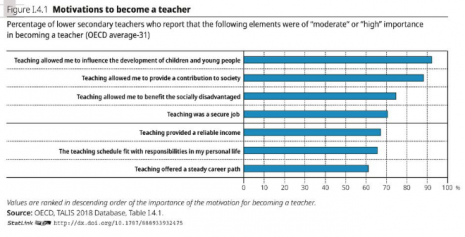

One positive result that emerged was that the strongest motivation to be a teacher was the chance to influence the development of children and young people. Two out of three said it was their first choice for a career. Primarily though, what the survey revealed is that the nature of teaching has changed, and we must be prepared to face the challenges and embrace the opportunities that have arisen in recent years.

Use of technology

The most striking difference between the results of 2013 and those of 2018 is the use of technology in teaching. This applies both to teachers using technology to help with lessons, and to pupils being taught how to use it. Nearly 80% of teachers said they’re using it more overall than in previous years. Meanwhile, the frequency with which teachers have students use ICT has risen across almost all OECD countries since 2013, to the point where 53% of teachers say they frequently or always use this practice. Richard Culatta, CEO of the International Society for Technology in Education, highlighted how innovation could be a great way to stop teachers feeling isolated in their classrooms, and should be taken full advantage of (something we at Bridge have always believed).

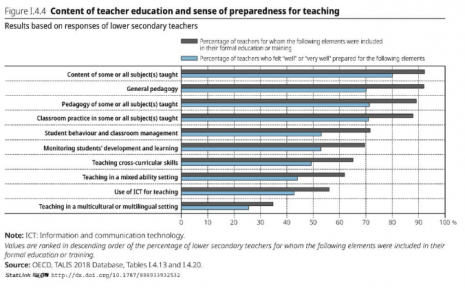

Despite this increase, teachers are still not getting the support they need to use the new classroom technology. Only half of teachers said that technology was included in their training, and less than half reported they felt “well” or “very well” prepared for the use of ICT in teaching. Perhaps this is indicative of a wider reticence in the education sector to fully engage with technology, unnecessarily fearing the automation of the sector. It’s an issue that has been recognised by many educational leaders; Anthony Salcito, VP of Education at Microsoft, said we need to ‘remove fear’ from technology by making it less complicated. It is of course important that the appropriate support network is developed so that when technology is introduced teachers are equipped to use it confidently and effectively.

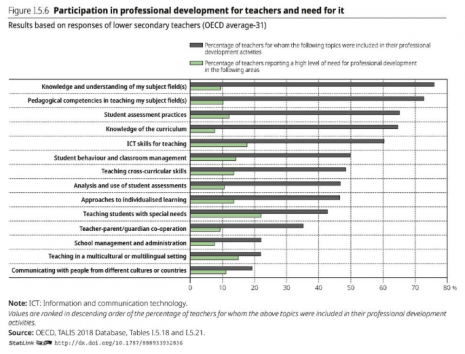

In addition to their training, just over 60% of teachers surveyed for TALIS reported that ICT skills for teaching were included in their professional development activities, while around 17% reported a ‘high need’ for this.

How much time is actually spent teaching?

Further to the need to train and support teachers to understand and use technology, TALIS revealed that teachers are spending less time teaching. During an average lesson, 20% of their time is now spent keeping order or doing classroom admin, an increase since 2013. As a result, less time is going into teaching and learning. They also spend just over half of their working time teaching lessons, suggesting that planning and marking are extremely time-consuming.

These statistics vary depending on the environment. On average across the OECD, teachers working in privately managed schools spend significantly more time on actual teaching than their counterparts in publicly managed schools. This may relate to the fact that teachers tend to spend less time actually teaching when in overcrowded classrooms, which was recognised by teachers as an overriding problem: a poll on spending priorities saw ‘reducing class sizes by recruiting more staff’ as their top priority (even beating increasing teacher salaries!).

What about the shortage of teachers?

Assessing the evidence, the OECD gives pointers on how to move forwards. A big finding in the survey is SDG4 point C: ‘to substantially increase the supply of quality teachers.’ TALIS suggests that in order to meet this Goal, countries must be willing to offer new avenues into teaching while preserving quality training, ‘including fast-track or alternative routes.’ OECD special advisor Andreas Schleicher points out that to solve problems countries must be willing to explore all avenues. ‘Competition and collaboration [should not be] placed as opposite ends. The most successful countries have systems that harness and balance both!’

What can we learn from TALIS 2018?

Broadly speaking, this report is about lower secondary schools in ‘rich or developed’ countries, and it doesn’t offer any specific insights for the countries where Bridges operates: Liberia, Nigeria, Uganda, Kenya, and India. What’s striking however, is the parallels to the problems these countries face and the solutions to some of these challenges offered by the Bridge approach. Regardless of where the school is, technology can be used to support, improve and empower teachers to deliver learning. It is clear that teachers join the profession in order to teach, increasing their fluency with technology will enable them to focus on achieving that ambition and a, “chance to influence the development of children and young people,” in their communities.

The shift towards technology can benefit teaching and learning, and teachers are willing to adopt new methods—especially where it gives them more time to actually teach!

There needs to be careful consideration given to how you introduce technologies and the subsequent training, support and continuous development of teachers, necessary for maximising the potential of technology in the classroom; the urgency is only heightened by the startling realisation that by 2030, we’ll need to have trained and supported 69 million brand new teachers in addition to the challenges that already exist.