Early childhood development in a developing country context

6 August 2019

As our understanding of psychology and human development has become more sophisticated, there’s been an increased focus on the importance of early childhood development (ECD). The World Health Organisation defines this as the ‘physical, social, emotional, cognitive, and motor development’ of children between 0-8-years -old. These early years are critical because it’s the time when young brains are developing most quickly—forming more than 1 million connections each second—laying the foundations for the rest of a child’s life.

Such is the importance of ECD that it was included in the 2015 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), confirming its growing significance as part of the global development agenda. The second target of Sustainable Development Goal 4 seeks to ensure that, by 2030, “all girls and boys have access to quality early childhood development, care and pre-primary education so that they are ready for primary education.”

The SDG framework explains that this goal is critical to ensuring children’s long-term development, learning and health. It outlines how: “Investments in young children, particularly those from marginalised groups, yield the greatest long-term impact in terms of developmental and educational outcomes.” It also enables early identification of disability, which can lead to better interventions and better learning outcomes.

Why is early childhood development important in the developing world?

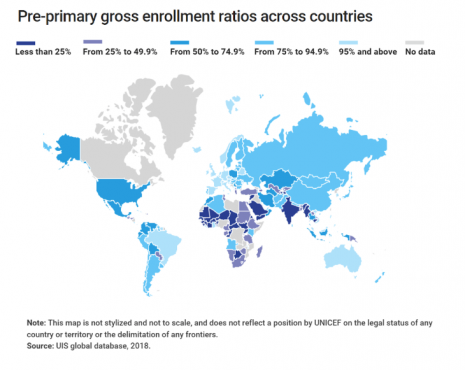

Overall, ECD has been on an upward trajectory: since 2000, pre-primary education has increased by almost two-thirds and the gross enrolment ratio increased from 32% in 2000 to over 50% in 2017. However, there’s a gaping disparity between ECD investment in higher-income countries and that in lower and middle-income countries. World Bank 2016 estimates reveal that 250 million (43 per cent) of children in low and middle-income countries were held back from reaching their full capacity. For example, of 27 countries in Sub-Saharan Africa that were measured, only 0.01% of gross national product was spent on pre-primary education in 2012.

However, a focus on ECD in developing countries is becoming more urgent than ever before. By 2050, Africa is expected to account for more than half of the world’s population growth. By 2100, if current trends persist, around 50% of the world’s children will be African.

The economic argument

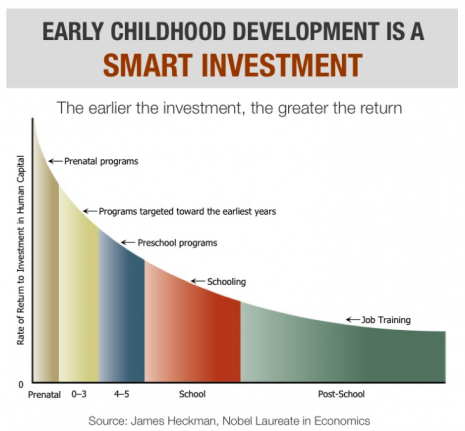

Learning begins at birth. ECD interventions have proved to be the foundation for later learning, academic success and productivity. A study on increasing pre-school enrolment in 73 countries found higher future wages of US$6 to US$17 per dollar invested, which indicates potential long-term benefits ranging from US$11 to US$34 billion (UNICEF).

In human capital terms, we need look no further than Nobel Prize-winning economist James Heckman; who produced the ‘Heckman Curve’ to show that the highest return on investment in education is in pre-primary learning, from the ages of 0-3-years-old.

Moreover, supporting ECD is a great investment for governments in developing countries. New research has shown that the return on investment for ECD can be as high as US$13 for every US$1 spent, and those children in lower and middle-income countries who experience high quality ECD learn more in primary school and can earn up to a quarter more in wages as adults.

While the polarity in investment in ECD might paint a bleak picture of the current state of inequality, a drastic change in policy means that ECD could actually help to redress this imbalance. Extensive research shows that implementing ECD strategies can help to close the inequality gap that begins at birth. For babies born into deprivation, intervening early can reverse harm. Meanwhile, when children are receiving ECD, mothers in low-income families have the opportunity to work or continue their education, which will have both long and short-term benefits for the whole family.

Getting to a point where all children have equal access to ECD will require a concerted effort across many fields. The BMJ recognises the need for the involvement of both the public and private sectors, as well as civil society. The SGDs have given momentum to the push for ECD investment, and this opportunity must be taken full advantage of.

Early childhood development in developing country contexts

The context in which children grow up, develop and are educated in the developing world can be very different to the experience of a child growing up elsewhere in the world—especially in the west.

Violence and conflict

“Violent discipline is widespread in many countries,” writes UNICEF, a sad reality for many children and schoolchildren in developing countries. This experience has negative consequences for a child’s development and can lead to ‘toxic stress’ which interferes with the brain development of young children.

Conflict and uncertainty also play a role as children younger than five in conflict-affected areas and fragile states face elevated risks to their lives, health and wellbeing. The 2015 report Building Better Brains includes a recommendation that safety is, “a prerequisite to early childhood development.”

Play

Aspects of ECD vary from country to country, and when teaching ECD it’s important to be conscious of these differences. For example, when it comes to playing, Western psychological theory primarily emphasises cognition, whereas anthropological studies in Africa have shown that play additionally serves to teach cultural practises from a young age. Observing play in rural and metropolitan areas of Zambia, one sociologist notes that children’s play in these areas is very inclusive, bringing in children of all ages and physical abilities.

Music

Meanwhile, music and dance are of great importance for many African cultures, and function similarly to play in the way they operate as a type of induction. Children in most African cultures participate in both from an early age. They share a communication role in human life; there is a strong connection between music and language, with studies showing music as having a notable impact on language and reading abilities.

Language

A lot of countries have multiple languages, and this can complicate how ECD should be delivered. Research has shown that when an unknown language is used in instruction, learners struggle to integrate the meaning of new words with what they already know. Its therefore been argued that teaching in the mother tongue helps young learners make connections more easily. The SDG framework dictates that multilingualism is fostered, starting with early learning in the first language of children.

However, this is not always a straightforward process. In India, for example, multilingualism is very much ingrained in the culture, and there isn’t one common language that supersedes all others, which poses a problem for teaching ECD, particularly in metropolitan areas. In some schools, children are taught in their home language for some activities and for other activities, they are taught together through a common language. In other schools, the building is divided into different language areas. The teachers are generally fluent in several languages.